Back in 1962, a young new director made a programme for the BBC on the life of Edward Elgar. His name was Ken Russell, and he was supported by Huw Wheldon, with whom he co-wrote the commentary, Ken Higgins who photographed it, and Humphrey Barclay, who produced it. And that was about it, the whole thing was made by no more than half a dozen people.

I well remember seeing this programme when it was broadcast, and being totally bowled over by it. Russell went on to bigger things in TV and films, even making several more musical tele-biographies, on such diverse characters as Tchaikovsky, Delius, Bartok and Prokoviev. They may have been bigger, and more extreme, but, to me, “Elgar” was a work of televisual perfection.

Some clever soul on the Sky Channel “Artsworld” scheduled it to be repeated the other night, and it was with some trepidation that I watched it again, 44 years later. I was 16 when I first saw it, and must have watched it then through juvenile, almost childish eyes. It has remained with me in my mind over the years, as a classic piece of Television – one which you felt really was a landmark in the medium. My viewpoint in 2006 would be from a very different point, and my worry was that, on seeing it again through 60 year old eyes, it would be a real disappointment.

I really needn’t have worried. I found it still a quite superb piece of work, and a real marker to the documentary makers of today, who mostly seem to have lost the simplicity, the beauty, the glorious photography, the stunning direction, the perfect pace and the eloquent, understated commentary contained in this little jewel of a programme.

For the first time on television, Russell managed to get the BBC documentary administrators to accept the use of actors in such a programme. We saw Elgar acted out firstly as a young man, changing to a 40 year old man, just married, and finally in his old age as he gradually became almost a recluse in his beloved Worcestershire. Given the subject, the choice of a soundtrack was blindingly obvious, and Elgar’s quintessentially English music, be it the Imperial Marches, the gentle Serenade for Strings, his Second Symphony and the glorious Cello Concerto was allowed to thread its way through the story.

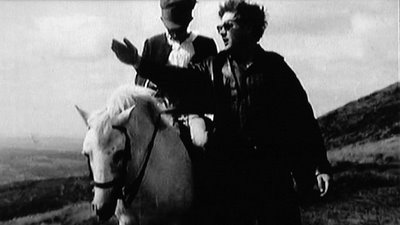

One of Russell’s images, that of young Elgar galloping on a pony along the top of the Malvern Hills to the accompaniment of the Introduction and Allegro, is simply the best fit of music and image I have ever seen. It drilled its way immediately and permanently into my mind. Every time I’ve listened to that piece since seeing this programme, the picture of a boy on a horse flowing across the top of England appears in my mind. Quite magical.

Some clever soul on the Sky Channel “Artsworld” scheduled it to be repeated the other night, and it was with some trepidation that I watched it again, 44 years later. I was 16 when I first saw it, and must have watched it then through juvenile, almost childish eyes. It has remained with me in my mind over the years, as a classic piece of Television – one which you felt really was a landmark in the medium. My viewpoint in 2006 would be from a very different point, and my worry was that, on seeing it again through 60 year old eyes, it would be a real disappointment.

I really needn’t have worried. I found it still a quite superb piece of work, and a real marker to the documentary makers of today, who mostly seem to have lost the simplicity, the beauty, the glorious photography, the stunning direction, the perfect pace and the eloquent, understated commentary contained in this little jewel of a programme.

For the first time on television, Russell managed to get the BBC documentary administrators to accept the use of actors in such a programme. We saw Elgar acted out firstly as a young man, changing to a 40 year old man, just married, and finally in his old age as he gradually became almost a recluse in his beloved Worcestershire. Given the subject, the choice of a soundtrack was blindingly obvious, and Elgar’s quintessentially English music, be it the Imperial Marches, the gentle Serenade for Strings, his Second Symphony and the glorious Cello Concerto was allowed to thread its way through the story.

One of Russell’s images, that of young Elgar galloping on a pony along the top of the Malvern Hills to the accompaniment of the Introduction and Allegro, is simply the best fit of music and image I have ever seen. It drilled its way immediately and permanently into my mind. Every time I’ve listened to that piece since seeing this programme, the picture of a boy on a horse flowing across the top of England appears in my mind. Quite magical.

Elgar’s story of accepted greatness only started in Germany, just after the turn of the century, where he became wildly popular, well before England took him to their hearts. Russell picked up the conflict and pain in Elgar’s mind which resulted from England taking up his “Land of Hope and Glory” as a jingoistic military anthem against the Germans, who had given him so much help and approval in the previous 10 years. No wonder he grew to hate the piece.

Huw Wheldon’s commentary is a model of clarity, always informing and supportive, explaining and guiding the viewer’s understanding - but always understated.

Overall, however, we see a documentary maker of genius at work. Russell is never afraid to use a startling image to make his point. Just look at the sureness of hand and the power in the two images below.

The light and shade in the pictures (it was of course shot in Black and White) show an almost painterly approach to the subject, and Russell is not afraid really to hold an image, and let it breathe for a long time as the point he is making gradually unfolds. As an instance, he uses a simple Poplar wood, shot looking firstly upwards, and very slowly panning downwards to show the back view of a couple, Elgar and his wife Alice, walking into the distance. With no words, just the Cello Concerto playing as a sound track, he paints a picture of the pair of them retreating into the Worcestershire countryside, moving away finally away from the pressures of London life. Very effective.

All in all though, a real eye-opener of a programme. I enjoyed it immensely. If you get a chance to see it, take it. You will not be disappointed.

All in all though, a real eye-opener of a programme. I enjoyed it immensely. If you get a chance to see it, take it. You will not be disappointed.

Tags:

5 comments:

Dear Rogerc, I enjoyed your piece on Elgar, and I'm sure my father would have done so to. I have recently transcribed a portion of a lecture he gave in 1976 in which he described the genesis and creation of the film. If you would like to read it, i can either leave it as a comment (though it is 1200 words) or email it. my email is wpw@hotmail.com.

Wynn Wheldon

Dear Wynn and Roger, I'm writing the authorised biography of Ken Russell. I enjoyed the article but it was quite a shock seeing Anne James' great production photos - I was hoping they would be among the rarities in the published book.

Wynn, I was at the Monitor reunion at the BBC where you read out one of your father's letters. I would love to have a transcript of the essay you mention in this blog. And perhaps talk with you about your father's work.

best wishes

Paul Sutton

Paul - I've only just picked this up, and that hotmail address died a long time ago. this is my new email: wpw@mendozafilms.com - wynn wheldon

Is the Elgar documentary available in the USA? It's one the best things Ken Russell did; must have introduced a lot of people to great music in general.

John Shepherd,

Boston

I tried watching Elgar on You Tube the other day and could not - I couldn't bear Huw Weldon's strangulated voice. The script needs to be re-voiced by a professional narrator - I am available. Rory Johnston, Hollywood Cal. rory7@sbcglobal.net

Post a Comment